Well-skilled to weave: The lace-making journey of Nicol Young.

From Newmilns to Gouverneur, via Daybrook and Philadelphia – the story of the men and women who made Nottingham Lace in America.

It has the makings of a rather long-winded pub quiz question…

What links the following places?

- The valley of the River Irvine in Scotland

- The city of Nottingham, England

- The Nottinghamshire county towns of Beeston and Arnold

- The city of Philadelphia PA

- The American communities of:

- Gouverneur, Kingston and Patchogue NY

- Chester, Scranton and Wilkes-Barre PA

- Pawtucket RI

- Tariffville CT

- Zion IL

It’s possible there may be other connections, of course, but my categoric answer is that this disparate list of places are linked by ‘Lace’. More specifically, all of these towns, villages and cities came to manufacture the product known to the world as Nottingham Lace. As told in this story, these communities are also connected by the hundreds of men and women who travelled thousands of miles around the world in the service of mass-producing this decorative textile.

As far as I can tell, the human stories of those migratory lace workers have largely gone unnoticed, but they were silent battalions who helped put ornate curtains at the windows, and picot-edged cloths on the tables of the Victorian and Edwardian world.

This is primarily the tale of just one of those men, a single foot soldier in the ranks of a world conquering army. I have chosen to tell it, specfically, because of a relatively obscure personal connection, one that will be explained as the narrative unfolds. However, this story also offers us the opportunity to delve into the many adventures of other individuals who shared similar journeys, and also to find out about long-lost industrial worlds that have left both a physical and a demographic mark on our own time.

Part One – A Journey begins.

On Wednesday 27th February 1907, nine days short of his thirty-fifth birthday, a Lace Maker called Nicol Young walked up the gangplank of United States Mail Steamer, the SS Noordland, at the port of Liverpool. The ship was moored at the Prince’s Landing Stage1 and she was looking her age, as smoke bellowed from her single black funnel. The funnel sat somewhat at odds with the ship’s four rigged masts that were throwbacks to the ‘old world’. First launched in 1883, the Noordland was destined to be taken out of service and scrapped the following year. Now, bearing the eagle insignia of the American Line, she was embarking upon one of her last transatlantic crossings; a two-week passage to Philadelphia, via the Irish port of Queenstown. As he felt the vibrations from the engine rattle through the steamer’s superstructure and imbibed the sights and sounds of the ship: the busy docks and the crowds of well-wishers waving them on their way, Nicol was, no doubt, experiencing both excitement and trepidation. Whether he had planned his trip meticulously, or he was leaving himself to fate, we don’t know… but it is likely that the story of his time in the United States didn’t, in the end, turn out to be one that he would have chosen to write for himself.

Although he was a native of Scotland, with roots in the Irvine Valley, a region with a rich pedigree for weaving and, more recently, lace making; Nicol had actually travelled to Liverpool from Daybrook, a small suburb of the town of Arnold in Nottinghamshire, at the heart of the English Midlands.

Daybrook was the place he had called home for the last twenty-years or so. Arnold, incorporating Daybrook, also had a significant hosiery trade. Nicol’s father, George, a Lace Weaver himself, was the man who had brought the whole family to Nottinghamshire … moving south from the village of Newmilns, Ayrshire in the early 1880’s. At first, they had settled in the villages of Greasley and Kimberley, before moving on to Arnold. So, in a sense, Nicol was already a migrant, even before he had set foot on the ship.

Now, Nicol was just one man lost amongst hundreds of the Noordland’’s steerage passengers (the ship could accommodate up to five-hundred third-class travellers, alongside one-hundred-and-sixty in the second-class cabins)2. He was travelling alone, having left his wife of eight years, Mary Ann, back home in Daybrook… for now at least.

Part Two – The Golden Goose.

Like many of the steerage passengers undertaking the journey with him, Nicol was travelling for economic reasons. We don’t know exactly what he had in mind, of course, but it is likely he was just seeking modest financial betterment for him and Mary Ann. However, he was only human, so it’s possible that he could have been harbouring dreams of striking it lucky and make his fortune in, what many saw as, the land of opportunity across the Atlantic.

Nicol was a cotton lace maker, which essentially means that he operated the machinery that made the lace3. Nottingham Lace was famous world-wide and was especially renowned at that time for its lace curtains and tablecloths. Whilst it is true that, in those years, the lace industry in Nottinghamshire had not yet plunged into total decline (that would be precipitated in later years by the Great War), its position as a world leader was most definitely being challenged. Virtually all production was now mechanised, and foreign competition was starting to make a real impact on the market. By the turn of the century, one of those countries trying very hard to muscle in on Britain’s place at the head of the lacemaking pecking order, was America.

Of course, it was not unusual for individuals and families to seek new horizons, even to emigrate, for the sake of economic stability; this had been happening for centuries. However, for non-native industries trying to establish themselves in new locations, immigration was a way to bring in the essential expertise and ready-trained labour necessary for them to hit the ground running. When it came to lace making at least, this population merry-go-round had, in the past, resulted in people moving largely between Britain and Europe… to Germany and France in particular4. Calais, for instance, had a thriving mechanised lace industry which had historically attracted migrants from Nottingham and vice versa.

In an interview in the Nottingham Post dated 28th August 2021, Dr. Josephine Tierney, from the University of Nottingham, a post-doctorate researcher on the topic, cited Nottingham families who had travelled to Patchogue, Long Island, in the United States, between the middle of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century for this purpose. It worked the other way around too. Nottingham was, after all, the world leader in the manufacture and trading of lace, and there are records of American families emigrating to Nottingham to work in the industry there.

As well as a growing lace trade, America had other attractions that would appeal to a young man of Nicol’s generation. The lure of American mythology had already begun to embed itself in the British psyche through literature and the media of the day. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows had been touring the UK since 1887 and had only recently finished a tour in 1906. The ‘Western’ movie was already established as a genre, in fact it is believe that the first movie of this type was actually made in Northern England in 18995. It all added to the appeal of the New World for anyone thinking of trying their luck across the Atlantic Ocean

The lure of the American mythology aside, there were a couple of very sensible reasons why Nicol had chosen to sail to Philadelphia. Firstly, for a lace maker, it appeared to be a good choice based on opportunity alone. The manufacture of textiles was the largest industry in the city, ahead of shipbuilding and the railroads. The textile industry also incorporated a growing lace making sector – one of the largest in the US.

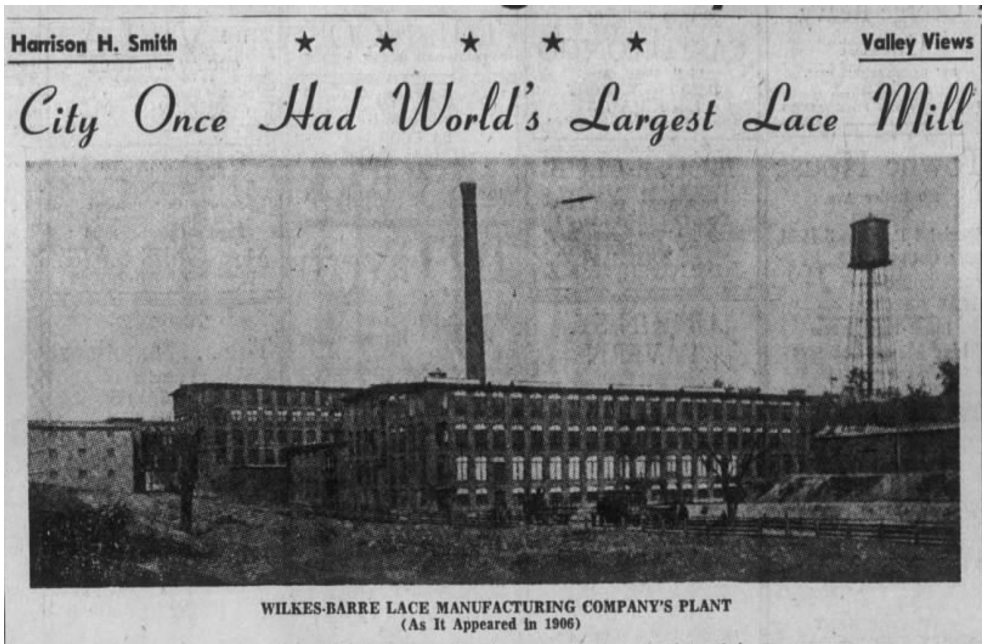

The Federal Government had been increasing tariffs on Nottingham Lace incrementally since the 1890s. At that time Nottingham had a virtual monopoly on provision of the machinery that produced lace curtains 6. However, the tariff changes had encouraged the birth of a home-grown lace industry, and, by 1907, there were several lace mills operating in Pennsylvania. This included two in Wilkes-Barre (the first founded in 1886), one in Scranton and three in Philadelphia itself (according to Dr. Tierney) – including the mill purchased by Joseph Bromley in 1894, located on the corner of North 4th Street and West Lehigh Avenue.

(Free Library of Philadelphia)

Bromley had obtained assistance in his venture from a Nottingham native called Sir Ernest Jardine (pictured left) 7. Jardine, who was later the MP for East Somerset, was an industrialist, whose company made and exported lace making equipment. Other Nottingham lace workers had already made the move there. Seasoned lace worker John Bowley emigrated from Nottingham to the US in 1893, taking his whole family with him 8. Bowley worked initially at the mill in Patchogue, Long Island, before relocating to the town of Chester, adjacent to Philadelphia. Here he was instrumental in starting up the Chester Lace Mill. So, it seems that there were both opportunities for employment in the lace or hosiery industry and long-standing Nottinghamshire connections in ‘Philly’ which Nicol might have been able to leverage if he needed to.

This Nottingham ‘connection’ also, most obviously, came in the form of the type of lace that many of these mills produced: Nottingham Lace. It was a brand that was known worldwide.

I think it’s time for a second pub quiz question then… “What was – or is –Nottingham Lace?”

The term Nottingham Lace entered the popular vocabulary towards the end of the eighteenth century, as entrepreneurs in and around Nottingham and Nottinghamshire sought ways to mechanise the production of ‘needle’ or ‘bobbin’ lace, which was largely a cottage industry during that period/ Lace-like fabrics had been around for thousands of years and it was probably introduced to Britain by Flemish immigrants. Nottingham, at the time, had a thriving hosiery industry making stockings using wooden frames. It was so successful that the number of workers engaged in producing stockings (sometimes whole families were involved) was exceeding the demand for stockings. Finding another way of utilising the frames, with modifications, to make lace, made sense to both alleviate the plight of the ‘stockingers’ and provide a ready-made skilled workforce. Following the invention of a frame adaption by John Rogers of Mansfield in 1786, the development of what were known as ‘point net’ machines took off, with new inventions appearing regularly well into the next century, which allowed for the production of finer, more intricate, patterns than those able to be produced by hand. This superior machine-made product was soon termed Nottingham Lace.9

It was originally called Nottingham Lace, therefore, because it was manufactured in Nottingham. So, could the term legitimately apply to lace manufactured in America, or anywhere else outside of Nottingham? Well, it would seem so… the term Nottingham Lace became synonymous with the type of product produced in Nottingham, rather than the geographical location where it was made. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines Nottingham Lace as “any of the various flat laces and nets machine-made originally at Nottingham, England and used for curtains, dresses, tablecloths”. Other definitions refer to the intricate designs and patterns including floral motifs and open spaces, which create a “light and airy effect”, or with scalloped or zig-zagged (picot) edges. Whatever it may have been in practice, identifying your product as Nottingham Lace in the early twentieth century gave it a certain cachet that was likely to make it even more desirable. Throughout the nineteenth century though, Nottingham remained at the centre of the mechanised lace-making universe.

Part Three – The Smiths, the Youngs and the Irvine Valley.

Whatever the employment opportunities that may have been waiting for him in Philadelphia as a skilled lace worker, Nicol also had another advantage over some of his fellow passengers: he had family already living in the city. Having someone close at hand who could help him get his bearings, and maybe even help with finding work must have been a great reassurance for him. The ship’s passenger list tells us that Nicol was travelling to join his cousin, Hugh Smith, who at that time was residing at 2133 West Somerset Street in the city. The house was a thirty-minute walk from the aforementioned Bromley mill. Before the year was out, Hugh had moved to 2917 North Marshall Street, which was even closer to the mill, only a ten-minute walk away.

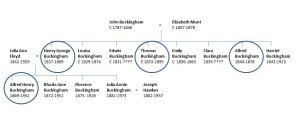

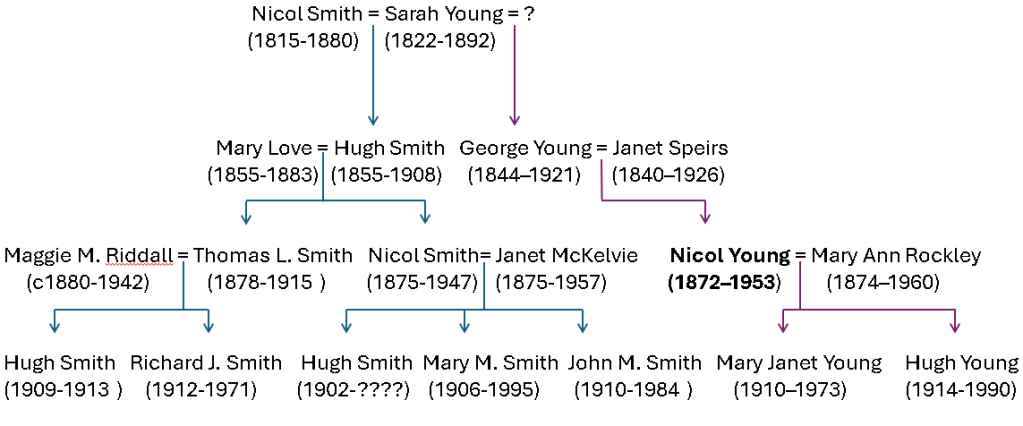

Hugh Smith was related to Nicol through his mother, Sarah Young. He and Nicol’s father, George, were half-brothers. Hugh was also an émigré Lace Weaver. He had travelled to the US in 1906 from the village of Newmilns, Ayrshire, where he had been born in 1855. As previously referenced – Newmilns had also been the village where Nicol and his family were resident prior to their move to England in the 1880s. Hugh’s son, also called Nicol, was residing with him in Philadelphia at that time too, he’d been there since 1902, together with his wife Janet, and two young children – a son, also called Hugh – and a new baby daughter, Mary (confusingly there are lots of people called Nicol, Hugh, Mary and Janet in this story – see chart below).

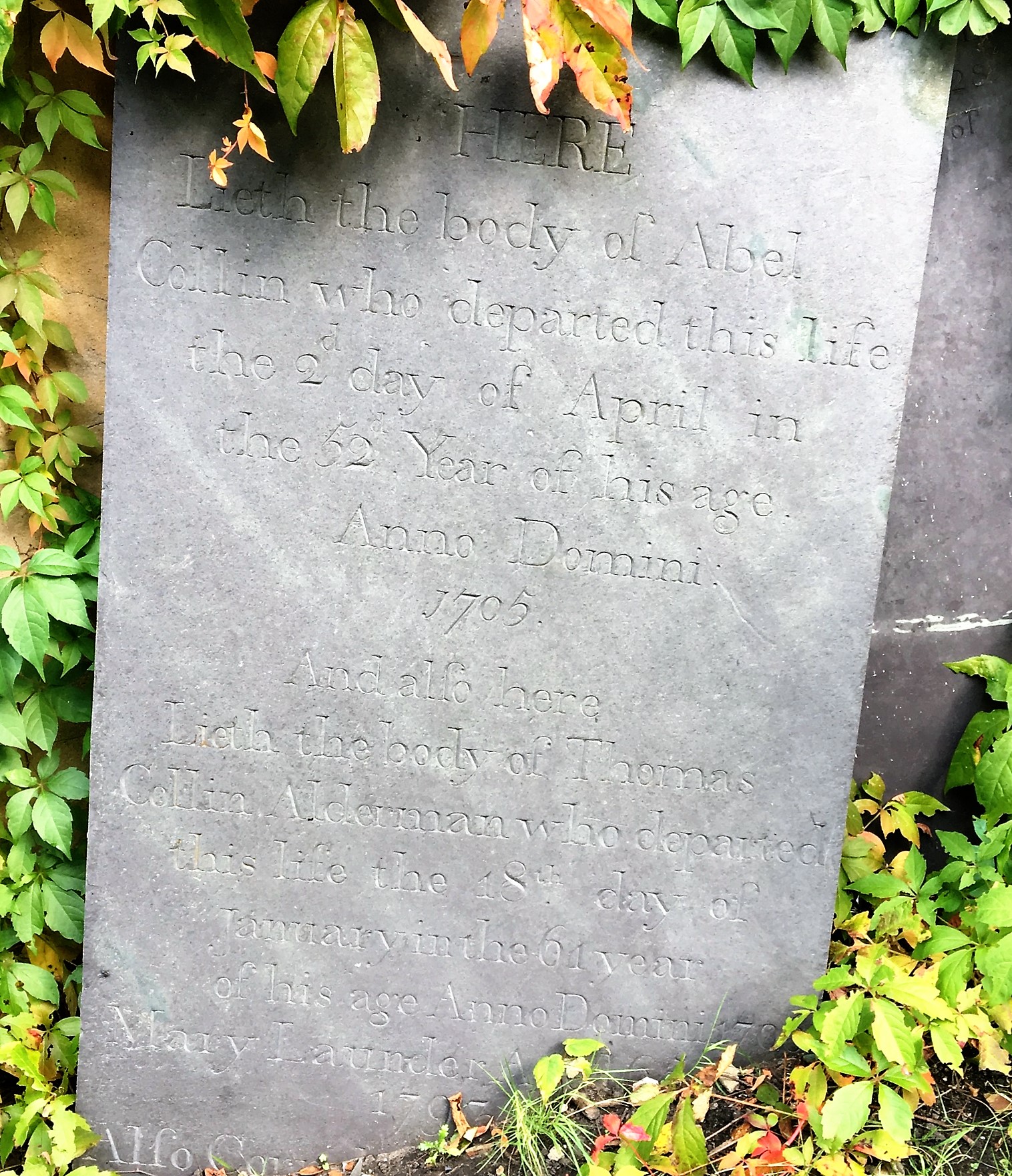

It’s probably worth spending some time at this point to discuss the history and geography of the Irvine Valley area, because it will feature again in this story. The aforementioned village of Newmilns is located on the north bank of the River Irvine, in the parish of Loudoun. It is around seven miles from Kilmarnock, which is the largest town in the area. Newmilns is sandwiched between the settlements of Galston (where Nicol was born in 1872) and Darvel.

I have already referred to the region’s weaving pedigree, which applied right across the villages and towns of the Irvine Valley. Historically, this had been built up by the area’s French Huguenot population. They had settled in Ayrshire after fleeing persecution in France at the end of the sixteenth century and had established weaving as the prominent trade in the valley. The industry boomed once Britain started to import cotton from the USA. As a result the population of the area, and urban expansion, grew in parallel with the prosperity of the towns.

However, this was a population in flux. For many years the Campbell family, who ran the Loudoun estate, had been taking advantage of demographic changes to grow the size of their farms in the area. Whilst this enabled them to employ more modern and profitable methods of farming, it also needed fewer tenants and less labour to work the land. This encouraged some families – from communities who had lived in the area for many decades – to look to Glasgow or even America for new opportunities. Pennsylvania was one of the top destinations for migrants to the new world from the Irvine Valley – meaning that there was already an immigrant cohort in Philadelphia, and nearby population centres, by the time that Nicol set sail. 10

To compound this trend, the introduction of the Jacquard power loom to the area in 1877 accelerated the automation of the weaving industry, resulting in increasing unemployment amongst weavers and a further decline in the population of the towns of the Irvine Valley. The Jacquard machine was considered by some to be one of the first examples of computer programming, using as it did punched cards to dictate which warps were raised at any given time. 11

To counterbalance this, Lace manufacture had been introduced to Newmilns from 1876, and it was to successfully establish itself during the next decade as more and more production was moved to the valley from the Nottingham area (some sources allege that this was an attempt by the lace companies to neuter the impact of Trade Union power12). Whilst this was good news for many Scottish hosiery workers, others, like Nicol’s father George had already decided that better opportunities lay elsewhere. For George, this meant taking his family not to Glasgow, nor abroad, but south to Nottinghamshire in the English Midlands: the home of the lace industry.

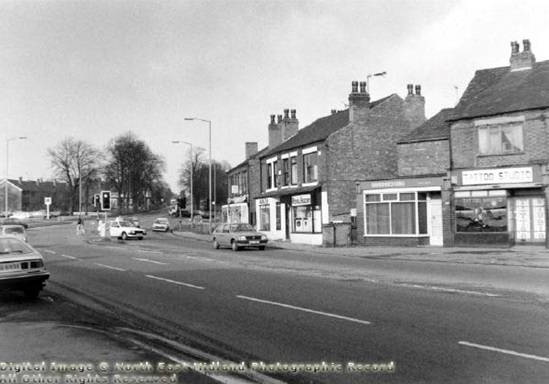

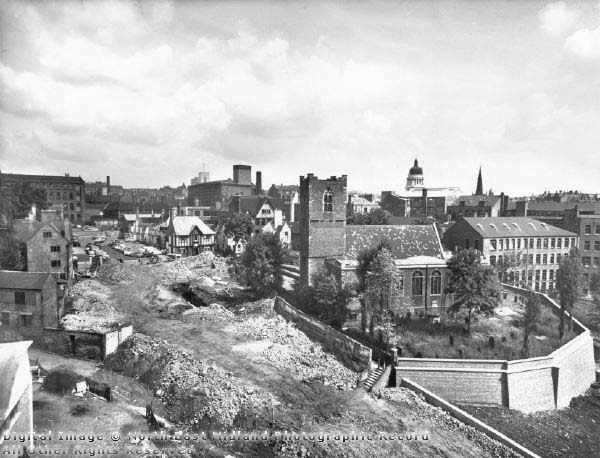

George and his family ended up in Arnold suburb of Daybrook. White’s Directory of Nottinghamshire records two lace manufacturers in Arnold as far back as 185313. Historically framework-knitters had formed a significant percentage of Arnold’s working population (including some of my own ancestors), so there was a ready workforce for this type of endeavour. As Daybrook expanded with the help of the Robinson family and the coming of the railway, in the latter part of the nineteenth century, this former tiny hamlet hosted the development of hosiery factories of its own14.

It is perhaps also worth noting that, at that time, the move of lace workers from Scotland to Arnold appears not to have been a commonplace occurrence, certainly not for weavers and lace makers, despite the town’s hosiery factories. Excluding the Youngs, the 1901 census records only eleven households with at least one member born in Scotland. Only one of these individuals had any connection to the hosiery trade (a ‘blouse maker’). The Youngs were the only lace makers amongst the Scottish émigrés listed in Arnold. By the time that Nicol felt that it was time to consider his own future, some 20 years after the family’s original move away from Scotland, it was America that beckoned.

Part Four – Philadelphia.

The Noordland”s crossing of the Atlantic was beset by strong winds and gales, at least for the first part of it’s journey, although the weather improved in the early part of March15. Whether he found his sea legs or not, Nicol arrived safely in the port of Philadelphia on 14th March 1907.

As he stepped into the streets of this vast industrial metropolis for the first time, after negotiating Customs at the Immigration Station (Pier Fifty-Three) on Washington Avenue, what he encountered would have probably been mind boggling in comparison to what he had known back in Britain, just in scale alone… let alone getting to grips with new-fangled ideas like hot-dog sellers on the streets and the extensive mix of nationalities in the city.

Philadelphia was an immigrant city. Most of these migrants came from Ireland and Germany but, as we have seen, there was also a long-standing Scottish community. Philly’s population had rocketed from nearly eight-hundred-and-fifty thousand in 1880 to over a million by 1900 and twenty-thousand immigrants were still arriving each year 16. The confusion, noise and diversity within the Immigration Station after each vessel arrived can only be imagined. The station could accommodate a maximum capacity of fifteen-hundred people, and it’s eight inspectors could process three-hundred English speaking passengers per hour, but only one-hundred-and-fifty non-English speakers. Frederic M. Miller, in an essay called Philadelphia: Immigrant City, described the scene:

“The station naturally became one of the most colorful places in Philadelphia. Inside, for example, was a part of the examination room called the ‘Altar.’ Since under some conditions single women were prevented from landing, many hurried unions were celebrated on the spot. Outside, there was usually a crowd of entrepreneurs eager to charge the newcomers exorbitant rates for a variety of needed and unneeded services.”

Often these immigrants arrived with a job already secured, some of those worked to pay off their fare for the crossing. We don’t know if the case with Nicol, but the fact that Hugh and Nicol Smith were already in situ must have given him, at least, some hope that finding work wouldn’t be a problem. Other arrivals were taken in hand by their own communities. A Russian immigrant called Saul Kaplan arrived in Philadelphia aged 13 in 1890 and left a memoir describing his experiences 17. He found employment in a factory and was paid two dollars a week – and was also charged two dollars for his board! If there was a ‘Golden Goose’ in Philly, it would have to be worked hard for.

A blog in the US National Archives by Griffin Godoy describes the story of an Irish Immigrant to Philadelphia, a girl called Bridget Donaghy, who arrived in Philadelphia aged 16 in 1909, together with her 9-year- old sister18. They had been sent to the US by their family in Ireland, essentially to be raised there, in the hope that they could escape the ingrained poverty back home. The girls were taken under the wing of a distant relative. Godoy goes on to describe how different nationalities in the city looked after their own:

“Philadelphia became home to immigrants from all over Europe. Thousands of Germans, Italians, and Irish decided to make the “City of Brotherly Love” their community. They all dispersed and created their own city blocs. Most Italians flooded to South Philadelphia, whilst the Germans and Irish occupied neighborhoods in Kensington and Fishtown. Churches, markets, and housing were quickly built as immigrants acclimated to their new American life. As time progressed, urban “white flight” caused another dispersion in Philadelphia and many formerly Irish neighborhoods were transformed as the Irish population flooded to the south of Philadelphia in Delaware County.”

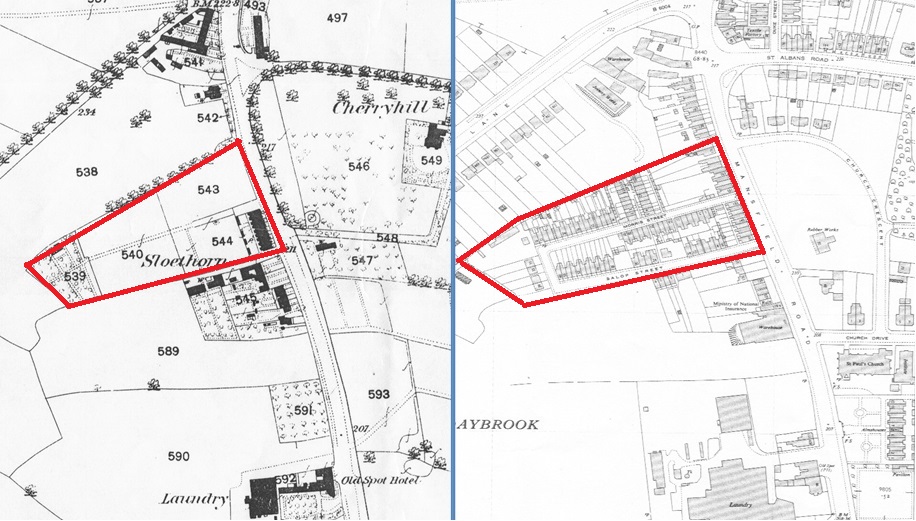

It is tempting to believe that new arrivals with links to the Irvine Valley were also part of a close and supportive community, and there is some evidence to suggest that this may have been the case. On the 1900 census for Philadelphia, there were one-hundred-and-two men and women who stated that they were born in Scotland and were lace workers. Virtually all of them lived in either Ward Thirty-Three or Ward Nineteen of the city – right in the area that 2133 West Somerset Street ,2917 North Marshall Street and the Bromley mill were situated, in suburbs known as Fairhill, North Philadelphia, West Kensington and Allegheny (see above map segment).

In the first few months following Nicol’s arrival, we can surmise that things went well, because Mary Ann followed him out from Arnold, arriving in Philadelphia on 30th June 1907 on the SS Friesland, an American Line sister ship of the Noordland. The Irvine Valley immigrant community was bolstered further on 14th October by the arrival – via Boston – of another of Hugh’s sons, Thomas Love Smith, and his wife Maggie. Prior to embarking from Glasgow on the SS Laurentian, they had been staying with Maggie’s family at the Angel Inn, Newmilns; their return to the US may be a further indication that there were jobs available for the newcomers. 19

Before too long, Thomas and Maggie, together with Nicol and Janet and their families, would go on to share another leg of their adventure with the Youngs but before then, a year after Thomas and Maggie’s arrival, events in Philadelphia took a sad turn. On 15th November 1908 Hugh Smith Senior died of Pneumonia, aged fifty-three years. Phthisis (Pulmonary Tuberculosis) was stated on the death certificate as a likely contributory factor, so he probably had been ill for some time. He was buried at Greenmount Cemetery two days later.

The sadness of Hugh’s death was compounded by the fact that Maggie was pregnant with his grandchild. She gave birth to a son on 4th February 1909, who was also named, perhaps unsurprisingly, Hugh.

Things got worse the following month. On 24th March 1909 Nicol Young’s younger brother, George, died, back home in Daybrook, also as result of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. He was twenty-six years old. We don’t know, of course, how long it took for this news to reach Nicol. This was a time before the telephone was in common use, so urgent messages were sent via Telegraph. Whilst sending the message – even across the Atlantic – could be relatively instantaneous, there was still the human factor of getting to a telegraph station at one end and receiving delivery of the printed message, by hand, at the other. Things like time of day would also be a factor in this process. However, the news, when it came, would have been devastating. The fact that Nicol was so far away from home no doubt intensified his grief and, I’m speculating here, but I imagine that it may also have provoked some feelings of guilt too.

Thomas and Maggie’s new baby was baptised at the Gaston Presbyterian Church on 21st May 1909, a short walk from the house at 2917 North Marshall Street. By the time of the baptism, Mary Ann and Nicol Young were expecting a child too. What a rollercoaster of emotions they must have gone through in those weeks.

Elaine Ellison Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (PhilaPlace)

There is nothing that focuses the mind like a new baby, or the imminent arrival of one. Finances immediately fall under the microscope and other things come into consideration too – like living in a hugely populous city, where disease was an ever-present threat (Hugh Smith Senior’s Tuberculosis diagnosis being a case in point – TB was the leading cause of death in Philadelphia at that time20) and where employment was never guaranteed. In addition, industrial unrest was always simmering under the surface in the so called ‘city of brotherly love’. In the same month as baby Hugh’s baptism, violence scarred Philly’s streets, as the tram company brought in strike breakers over a dispute with the Motormen and Conductors Union. Trams, tracks and cabling were destroyed amidst claims of police brutality and many arrests21. Could these factors have played a part in Nicol and Mary Ann, together with their Smith cousins, taking the decision to move on again, and leave the the tainted air of the city behind? Or was the promise of increased financial rewards elsewhere that drove them… or maybe both factors together served to clinch the deal?

They weren’t alone in moving on. Of the one-hundred-and-two Scottish lace workers who had lived in Wards Nineteen and Thirty-three of the city in 1900, only twenty-four remained by the time of the 1910 census. An indication, perhaps, that the ‘golden goose’ now lay elsewhere. Things didn’t improve in Philadelphia and the industrial unrest that had been building up during 1909 was eventually to culminate in the fractious General Strike of 1910.

The three families chose to head up to the northern limits of New York State, to a place called Gouverneur, some three-hundred-and-forty miles away from Philadelphia, as the crow flies. It was a leap of faith, but then again, everything they had done up until this point had been one too.

Part Five – Gouverneur: “The Nottingham of America”.

The village of Gouverneur sits in north-west New York State, in the shadow of the picture-postcard pretty greenery of the Adirondack Mountains. It is located only thirty kilometres from the border with Ontario, Canada which dissects the St. Lawrence River. The river also gives its name to the administrative county that the village sits within. Then, as now, Gouverneur is served by the railway and, therefore, it is likely that the Smith and Young families travelled north by train. Today, if you travelled from Philadelphia to Gouverneur. it would be a minimum nine-hour trip, via New York City. In 1909 it would likely have taken longer, and you may have needed at least one stopover… in Syracuse perhaps?

The origins of Gouverneur can be traced back to 1787 when the New York State legislature sold parcels of land along the banks of the St. Lawrence River. Then it was no more than lines drawn on a map and given the name of ‘Cambray’. It wasn’t seriously settled until 1805. Gouverneur Morris, a United States Founding Father and former minister to France, subsequently purchased a significant volume of land in the area and the village was eventually renamed, not perhaps after Morris’s given name, but more likely after his Dutch-born mother’s maiden surname, which was also Gouverneur.

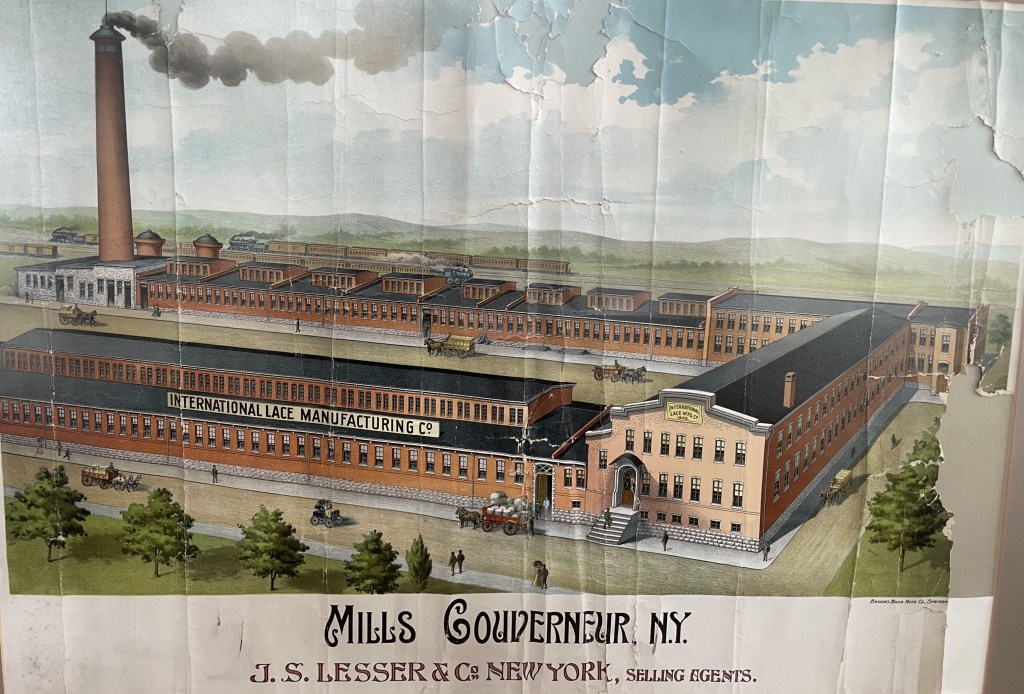

Up until the early part of the twentieth century, the village and wider town were mostly supported by industries that made use of the waters of the Oswegatchie River, which cuts through the village, to power lumber and talc mills. Mining of iron and pyrites, and quarrying, particularly of marble, also became more prominent as the 19th Century wore on. However, the reason that Nicol Young and his cousins headed here in 1909, was because of a new venture that had been unveiled some seven years beforehand.

The International Lace Company was constituted in Albany, New York in August 1902, partly in response to the favourable tariff position in the USA. The company’s major backers were Lesser Brothers of New York, who had previously specialised in importing Nottingham Lace. Now they were aiming to manufacture it on American soil. On the back of a prospectus issued by the new company, Gouverneur put itself forward as the perfect place to locate a factory. By October 1903 the factory had been built and production had commenced. The Ogdensburg Journal – which refers to Gouverneur as “The Nottingham of America” – described the scene in its issue dated 18th December 1903:

“The extent of the buildings would surprise many who have … not visited Gouverneur’s new industry. Occupying a commanding position on the west side of the Oswegatchie, they are a conspicuous feature of the place. Not until the visitor has gone over them, however, does he fully realise their extent. There are ten miles of water pipes in the building for heating and other purposes…

The offices in the front of the building are handsomely equipped. Here, as in other large factories, employees and visitors gain access to the mill. The long weaving shed… is a most interesting room. It is well lighted from sides to the top and here are spaces for thirty lace curtain looms. Six are in place, two more are on their way and seven more are to be imported within three months, making a total of fifteen which will be running in a short time.

A lace curtain loom is a lofty and complicated affair. High up among the skylights the patterns which are designed and made in a neighbouring department are inserted in the loom. The patterns control thousands of linen cords extending downward to the loom and multiply or drop threads as the weaving proceeds forming the pattern, the warp and woof being prepared and wound on spools, shuttles and cylinders in another department. Standing before the loom a person can see the flowers, figures and background of the curtains grow rapidly before his eyes.”

The article claims that the Gouverneur lace mill was, at that time, the largest in the world. It goes on the say that, once the additional looms were installed, the mill expected to produce three to four-thousand pairs of “Nottingham Lace Curtains” per day, produce one million dollars’ worth of product per year and employ about three to four-hundred people. That workforce, it says, … will be drawn from the resident population. Some of the operatives, Swiss and English, who have learned the trade abroad, get big pay. Gouverneur people will be given the opportunity to learn, and the prosperity of many natives will date from the establishment of the lace mill.”

The optimistic outlook encapsulated in the article didn’t entirely come to fruition. By 1905 only ten looms were in situ and the number of employees was at the lower end of the numbers predicted. In 1907 the company filed for bankruptcy, blaming the high price of cotton, and the mill closed for business.22

Part Six – A new begining.

The mill was rescued from oblivion in 1908. A group of “Philadelphia capitalists” 23 purchased the plant at a public auction and put together a bold plan to treble production and increase the number of people employed at the factory. It is not totally clear from reports, but it was well-known that the Bromley company of Philadelphia had designs on the plant, and it is at least possible that they were involved in the consortium to resurrect it 24. If so, then it might also have been the case that the call was put out to its workers in Philadelphia to help them pull together the expertise they needed to enact the plan. This was perfect timing for Nicol, Thomas and Nicol and their families.

We can’t be sure precisely which month they made the journey in, but there are clues that indicate that they probably travelled sometime between the Summer and Fall of 1909, this assumes that that the brothers and their cousin made the journey north either together, or within the same approximate time period. As a starting point – none of the three men were listed as employees of the lace factory in the Gouverneur village directory for 1907-1908. We also know that Thomas and Maggie were in Philadelphia at the time of their son’s baptism on 21st May 1909 and that the latest possible date that Nicol Young was resident in Gouverneur is likely to have been from around mid-November 1909 25. Furthermore Nicol Smith’s wife, Janet, took their children back to Scotland to visit her mother in April 1907, returning to the US, via Canada, on 9th November 1909. Janet stated on the immigration papers that that she was heading to Gouverneur, so her husband must have been resident in the village at that point. Whenever they arrived, it seems clear that they were seeking to take advantage of the wave of optimism brought about by the re-opening of the mill.

It probably wouldn’t have been a surprise for them to find that there was already a small community of Irvine Valley immigrants in Gouverneur. There were brothers James and Boswell Ross from Darvel, William and Mary Dykes from Newmilns and Kilmarnock respectively, plus the Dykes’ relation James Cox, who had also been resident in Darvel before sailing to the US in 1905. William Scott, another native of Newmilns, had been in America since 1899 and, like many of his colleagues, he had been based in Philadelphia prior to moving north. It’s entirely possible that the Youngs and the Smiths may have known some, or all, of these people prior to arriving in St. Lawrence County.

There were also a significant number of English lace workers in Gouverneur at that time, easily outnumbering the Scots. All the English lace workers were either from, or had connections to, Nottingham and Nottinghamshire. It is said that there were so many English people living in Gouverneur at the time that cricket leagues were formed in the area 26. I have told the individual stories of Gouverneur’s English cohort of 1910 in more detail, in Part Ten of this history.

It is into this community that a daughter – Mary Janet Young – was born to Nicol and Mary Ann on 28th January 1910. It’s probable that she was born at 100 Hailesboro Street, which was the house the family were living in at the time of the 1910 census (taken on 15th April). In fact most of this community of lace workers lived on Hailesboro Street or Prospect Street, which were the two closest streets to the mill (the main entrance to the mill was via Prospect Street).

Mary Janet Young – known simply as ‘Janet’ in later life – is my personal connection to this story and the person who piqued my curiosity enough for me to want to research it and write it down. You can find out why that was in my piece on my childhood in Daybrook, Nottinghamshire.

For many of the Scottish and English lace workers in Gouverneur during this period there was enough work for them to be confident enough to plant roots in America. Nicol Smith was one such individual. By 1910 he had already submitted papers seeking naturalisation. Indeed, most of this group ended up staying in America. Life wasn’t rosy for everyone, however.

A column on the 1910 census return records the numbers of “Weeks Without Work”. Where an individual had recorded a period of unemployment, with a few exceptions, it was generally in single figures. Nicol Smith, for example, records that he had been out of work for six weeks. For his brother Thomas, and for Nicol Young, that figure was significantly larger – twenty-four weeks in each case. Both men had young families to provide for, and the lack of income over such a period was clearly unsustainable. It’s clear that they must have relied on some form of community support in such circumstances just to get by.

It is easy to imagine how soul destroying that must have been. Nicol Young, with a baby to feed, must have known that his American dream had come to an end after less than three years. As a result, he and Mary Ann took the decision to return to England, leaving their cousins behind. Perhaps, the loss of his younger brother the year before had also focussed Nicol’s mind. They managed to scrape together the fare for the journey home 27 and, a few weeks after Mary Janet’s first birthday, they embarked from New York City on Cunard’s RMS Mauretania. The Mauretania, alongside her sister ship Lusitania, were the current stars of transatlantic travel, able to make the crossing in five to seven days – the ship was a world away from the Noordland that Nicol had arrived on in 1907. There were strong winds and gales in the North Atlantic during this period and, to start with, it was very cold, although becoming milder as they approached their destination. They docked at Liverpool on 28th February 1911. 28

Part Seven – The journey ends.

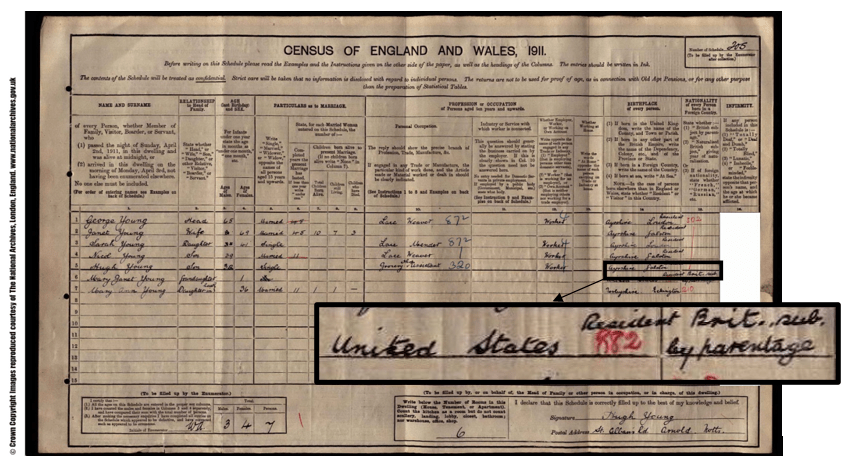

The Youngs had the (presumably) rare distinction of being recorded on both the 1910 American Census and the 1911 UK census. The latter was taken on 2nd April 1911. At that time they were resident at the home of Nicol’s parents, including a couple of his siblings (Sarah and Hugh), on St. Albans Road in Daybrook. It probably helped, space wise, that Nicol’s youngest brother, Matthew, had taken the opposite journey across the Atlantic, emigrating to Canada at about the same time.

Almost exactly three years later, on 17th April 1914, Nicol and Mary Ann added to their family with the birth of a son, who – not unsurprisingly for followers of this story – they named Hugh. At this time they were living at 37 Harcourt Road in the Forest Fields district of Nottingham. The house is only five or so minutes’ walk from the Birkin and Company Ltd. lace factory on Beech Avenue, so it is highly likely that Nicol worked there at this point. The company retained the factory until 2003. A description of the factory in its heyday, in many ways echoing the desccription of the Gouverneur mill in the Ogdensburg Journal, is available in an article from the Nottingham & Notts Illustrated magazine entitled “Up-to-Date” Commercial Sketches: Industries and Manufactures Illustrated and Reviewed dated 1898) 29:

“Entering from the “Forest” near the handsome Higher Grade School Board buildings, we are faced by a timekeeper’s office and some stabling to the left, beyond which is an old-fashioned, two-storied, ivy-clad house, once the residence of Mr. Richard Birkin, and now occupied by some of the firm’s employees. We believe Mr. R. Birkin still resided here at the period of his first mayoralty. Beyond the house is a second entrance to the works from Palm Street. Quitting the main entrance, we first arrive at the old factory, a substantial three-storey building, of which the ground floor is occupied as workshops for the punching or pattern-card making department of the “Levers” or fancy lace branch of the business, next to which are the winding and threading rooms, each fitted with the requisite up-to-date machinery. From here we pass to a large and well-lighted room, in which a number of boys and girls, known as threaders and bobbin pressers, are busily engaged; while in an adjacent apartment a staff of male hands is occupied in somewhat kindred labour. Crossing the yard, on the way to No. 1 factory, we approach a tall chimney stack with a turret clock displayed in its side and surrounded to about one-half its height by a winding stone staircase, with windows at frequent intervals…

Passing through to the open space in front of the engine-house, we come to the large modern four-storey building known as the New Factory, formerly occupied by the lace curtain machines, and which since their removal to Scotland has been utilised by Messrs. Birkin for the more modern part of their plant of fancy lace machinery. All the machines in this factory are of the latest type and construction, and on them are manufactured the very finest classes of goods capable of being produced by machinery. On the two floors there are twenty of such machines, each one of which, with its warp, represents a value of twelve hundred pounds. In ascending to the upper floor we note the substantial character of the walls and stone staircases and admire the lavatories and general sanitary arrangements provided on each floor for the comfort and convenience of the employees.”

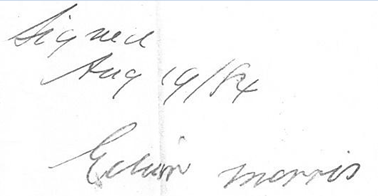

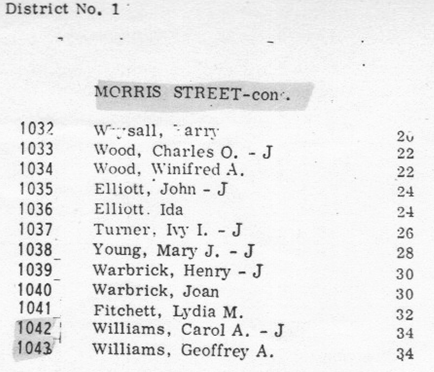

By 1921 the Young family was back in Daybrook and living at number 28 Morris Street, towards the top of a street that tumbled down a hill to the Mansfield Road. Nicol was working at W.H. Hurcombe and Company at this time. The company were located in a building known as ‘Jacoby’s Factory’, on Sherbrook Road. The company specialised in the manufacture of lace curtains. Nicol’s father, George, who was now retired, had also worked at Hurcombe’s, as did his sister, Sarah, who was employed there as a ‘Lace mender’.

Nicol and Mary Ann lived at 28 Morris Street for the remainder of their lives. Their daughter, Mary Janet – who was known simply as ‘Janet’ – continued to live in the house until the local authority decided that the street should be demolished as part of an urban renewal scheme in the early 1970s. As a child I lived a couple of doors along from Janet, and I clearly remember her distinctive presence. Her relationship with the local children was, to put it mildly, often fractious. I hope that this piece goes some way to putting her and her family in context and that it offers a corrective to the image of her that we had as children back in those days.

Nicol died in the house on 14th March 1953 at the age of eighty-one years. Mary Ann followed him almost exactly seven years later, on 24th March 1960, aged eighty-five. Mary Janet, who was born over three-thousand miles away in Gouverneur, New York, died on 19 April 1973, aged just sixty-three years. At the time she was resident at Hillcrest Hospital in East Retford, a home for the elderly and a former workhouse. It was situated thirty miles away from her last family home on Morris Street. All three of them are buried together in Redhill Cemetery, a short walk from where Morris Street once stood. There is a small memorial vase on the grave which commemorates Nicol and Mary Ann, but it makes no mention that Mary Janet is also buried there.

Part Eight – The decline of the lace industry.

The consensus amongst historians is that the 1914-18 war signalled the demise of the modern lace industry – certainly in the UK. The war disrupted production, with coal suppliers diverted to other industries better serving the war effort, meaning that lace factories couldn’t count on the power they needed to maintain production. On top of this, long-standing export markets, in countries such as Germany, were taken away at a stroke and the import of raw materials, such as cotton, were disrupted. The workforce was disrupted too, as key personnel went off to fight overseas.

This decline continued after the war, compounded by the imposition of international tariffs and changes in fashion. In the UK there was a short-lived boom when import duties were imposed on imported lace 30, but lace factories across the UK still closed their doors. Then there was a second war, bringing with it all of the disruption of the first. After the war, companies merged, diversified or just went out of business as the industry adjusted to the modern era.

In 1925 a representative of Messrs. Hayward, Limited, Court lacemakers, of New Bond Street, who had decided to shut down their business, summed up the impact of changes in fashion in an interview in the Manchester Guardian: “Women nowadays … want frocks that they can slip on over their heads, and instead of lace-trimmed lingerie they are wearing Milanese silk. The day of the great demand for lace passed with the full skirts, which could be trimmed with deep flounces of lace. I see no prospect of wide skirts coming back.” 31

In its prime the lace industry employed 25,000 people in Nottingham and was responsible for five-million pounds worth of exports. By the1970s the industry in the city employed no more than 5,000 people. 32

The pressures of changes in fashion – which applied to the use of fancy lace curtains and tablecloths as well as clothing – took its toll in the USA too. Amidst a general depression in the US textile industry, the doors closed on the Gouverneur Lace Factory again in September 1928. The mill, however, true to form, bounced back again. In January 1936 the production of lace resumed under the auspices of the Bromley Lace Company. A couple of years later, a hosiery division opened in the factory, making silk hose, and many of the old lace factory hands were re-employed. However, war, again, intervened. The hosiery division closed in 1940 due to difficulties getting hold of silk fibre from Japan. The lace division did continue, making camouflage netting for the armed forces, but as the war was coming to an end, the inevitable happened, and the lace factory closed for good on 16th March 1944. Despite this, the building still stands and, most recently, has been used as a warehouse for a paper manufacturing company. 33

In a magazine interview in November 1992, Shirley K. Tramontana, curator of a museum exhibition about Nottingham Lace manufacture in the US, stated that, at that time, the mill in Scranton, Pennsylvania was the only one still involved in its manufacture.34 The Scranton Mill, for a time the world leader in Nottingham Lace production, eventually closed for good in 2002.35

Lace is still made around the world, and it is still considered to be a luxury item. Production has adapted to cope with reduced demand and has taken advantage of new digital technologies 36 . Vast industrial complexes, fitted with intricate machinery and employing hundreds of people, are no longer required. As a consequence some of those old mills, like Jacoby’s factory in Daybrook, and the Seekonk mill in Pawtucket have been demolished or lie abandoned. However, others, like the Gouverneur factory, the Tariffville mill and the Zion Lace Industries facility have found alternative commercial uses. Several others, such as the Kingston, Scranton and Bromley/Quaker mills continue to serve their communities in other guises, re-purposed as residential or public spaces.

Bottom Left: The Seekonk Mill. Pawtucket, prior to demolition – courtesy Pawtucket Library Photostream. Bottom Right: The Kingston Lace Mill, which is now a housing complex for artists – Photo Courtesy RUPCO Inc.

Part Nine – The Irvine Valley Scots – class of Gouverneur 1910.

So, we have followed Nicol Young to the very end of his journey, but what became of the other Irvine Valley immigrants who, like Nicol, were plying their trade in the Gouverneur Lace Mill at the time of the 1910 census? And what happened to his cousins – Nicol and Thomas Love Smith – and their families, who he left behind there?

The lives of the brothers Nicol Smith and Thomas Love Smith, took very different paths. Both initially stayed behind in Gouverneur, and both added to their families there. John McKelvie Smith was born to Nicol and Janet on 10th November 1910, and Richard Smith was born to Thomas and Maggie on 7th May 1912. However, Thomas and Maggie took the decision to return to Scotland shortly after their second son’s birth. They departed from Portland, Maine and arrived back in Liverpool on the SS Scandinavian in December 1912. It wasn’t a happy homecoming.

Less than a year later, back in Newmilns, on 15th October 1913, their eldest son Hugh died of Meningitis aged just four years old. Thomas’ occupation was detailed as ‘Insurance Agent’ on the death certificate, perhaps indicating that he was struggling to find work in the lace trade. In early 1915 Thomas was committed to the Ayr District Asylum suffering from ‘Acute Mania’ (the manic phase of Bi-Polar disorder). He died on 21st March 1915 from exhaustion and broncho pneumonia, aged thirty-six years. Maggie lived on until her early sixties, dying on 10th September 1942. Their remaining son, Richard, died aged fifty-nine years on 12th January 1971. The whole family is commemorated on a memorial in Newmilns Cemetery. See right – Photo by Alice Stevenson (Dreameralilu) via Findagrave.com.

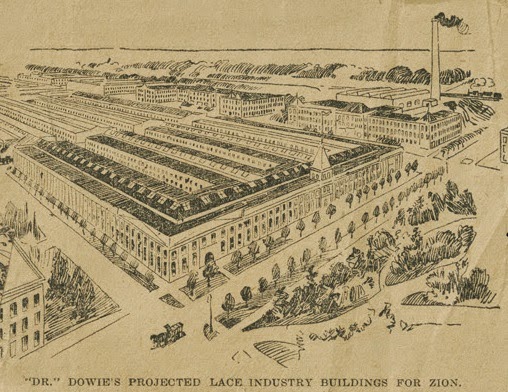

Nicol and Janet Smith, plus their three children became naturalised United States citizens on18th September 1912. At the time Nicol gave his address as Zion City, Illinois indicating that he was then employed by Zion Lace Industries, whose factory in the city was established in 1900. By 1920 the family had moved on again and were living in Pawtucket City, Providence County, Rhode Island, which possessed a lace mill run by the Seekonk Lace Company. By 1930 they had returned to live in Philadelphia, at 3031 North 4th Street (in Ward 33, close to where they had lived previously in the city). Nicol and Janet would see out there lives here. By then, it would seem that Nicol was struggling to find work in the lace industry and both he and son Hugh were running a Newspaper route (roughly the equivalent of a paper round in the UK). Son John, however, was a ‘helper’ in a Hosiery Mill and daughter Mary was a typist in an office. In 1936 Nicol and Janet made a final trip to back to Scotland. By 1940 Nicol was again recording his occupation as ‘Lace Weaver’, at the age of sixty-four and sons Hugh and John were now running the news dealership by themselves.

Nicol died of cancer on 29th January 1947 aged seventy-one. Janet survived him by ten years, passing away at the house they had shared together at North 4th Street, just around the corner from the Bromley mill, on 4th April 1957, aged eighty-two years. Both were buried at Sunset Memorial Park, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

With regard to their children – their son John eventually became a school administrator and died in Sun City, Arizona on 2nd May 1984 aged seventy-three years. Their daughter Mary married a Philadelphia Fireman in 1932 and raised two children in the city. Mary died on 12th September 1995 aged 88 years. At the time she was living in Warrington, a northern suburb of Philadelphia. Nicol and Janet’s eldest son, Hugh, born in Greenholm, on the opposite side of the River Irvine to Newmilns, in 1902, was working for the Philadelphia Post Office at the time of the1950 census. The obituary of his brother John in 1984 indicates that Hugh was still alive at that point, but I have been unable to trace what happened to him subsequently.

Of the other Irvine Valley Scots in Governeur in 1910…

Brothers James and Boswell Ross were natives of the Irvine Valley village of Darvel. At the time of the 1910 census they were both lodging with Thomas and Maggie Smith at 50 Hailesboro Street in Gouverneur. Both remained in the United States and saw out their final days in Gouverneur.

James (pictured left in a photograph from his passport application in 1919) was born on 11th October 1882 and naturalised as a US citizen in 1916. James had arrived in the US in 1906 and was listed as a Lace Factory employee as early as 1907-08. He married Jessie McCormack in Gouverneur in 1910. Jessie died in 1914 aged just thirty-nine. He married his second wife Faye in 1922 and became the father of a daughter, Betsey, the following year. He was still working at the mill in 1940. The only time he worked elsewhere was during the period 1928 to 1936, when production ceased at Gouverneur and James relocated temporarily to Scranton PA. James died in 1943, aged just 60. He is buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Gouverneur, alongside Faye, who died in 1987.

James’ younger brother, Boswell Ross (pictured right from a 1937 factory group photograph), was born on 9th July 1884 and arrived in the US a little later than James, in 1909. He soon began working at the lace mill. Around the period 1928 to 1936, when production ceased at Gouverneur, he joined his brother in relocating to find work in the mill at Scranton, Pennsylvania. Other than that, Boswell remained resident in Gouverneur. During this time he made several return visits to Scotland. He died on 17th May 1963, a couple of months short of his seventy-ninth birthday. He too is buried in the Riverside cemetery at Gouverneur.

William Dykes was born in Newmilns on 4th November 1879. He travelled to New York in 1901 and married his wife Mary Graham, who was also a Scot (from Kilmarnock), in Philadelphia in 1905. William and Mary were resident in Gouverneur by 1906, when their first child was born, although neither appear on the list of factory employees from 1907-08. He was naturalised in Philadelphia in 1917 after moving back to the city sometime post 1913. They lived at 3110 North Wendle Street for the remainder of their lives and worked at the Bromley/Quaker mill. They raised six children, one of whom – Hugh – became a fireman in Philadelphia. William died in St. Joseph’s Hospital, Philadelphia on 8th December 1947 aged sixty-eight. Mary lived on until a month before her eightieth birthday, passing away on 3rd January 1963. They are buried in the Greenwood Cemetery, Philadelphia.

James Cox was born in Darvel on 3rd May 1882. He travelled across the Atlantic the on the SS Majestic, arriving in New York from Liverpool on 3rd December 1904. James was a cousin of William Dykes through his mother Jean Dykes, and it was William that James had arranged to make contact with, in Philadelphia, upon his arrival. James was also listed on the employee roster for the Gouverneur lace factory for 1907-08. Around 1912 he married a fellow Scot, Helen Dunsmuir, and they went on to have three children. James was naturalised as a US citizen at Canton NY in September 1919. After the first closure of the Gouverneur lace factory in 1928, James took his family to Scranton, Pennsylvania, where they were able to find work in the large lace factory there, and where they were to remain. Helen died on 20 August 1952 aged 63. James passed away from cancer at the Medical Centre in Scranton on 14th February 1963 aged 80 years. James and Helen are buried together in Dunmore Cemetery, Scranton.

William Scott was born on 6th March 1877 in Avondale, on the north bank of the River Irvine between Kilmarnock and Galston. At the time he left for America he was living in Newmilns. He travelled to New York City from Liverpool in July 1898 and met up with his brother David who was already living in Philadelphia. He married English widow Bertha Beckett in Philly in 1908. Bertha already had a daughter from her previous marriage, and they added two sons to the family, both of whom were born in Gouverneur. After their sojourn in Gouverneur, they returned to Philadelphia around 1918, where they lived initially at 2928 North Fairhill Street. At that time William was employed by the North American Lace Company at 8th Street and Allegheny, which was very close to their house. By 1920 they were living on North 8th Street (even closer to the factory) before moving to 5961 Bingham Street, where they were to remain until William’s death on 5th November 1956 at the age of seventy-nine years. Bertha lived on at the house until her death, aged eighty-seven, on 3rd July 1964. They now lie together in Lawnview Cemetery, Philadelphia.

Part Ten – Gouverneur’s English community of 1910.

I have previously referenced the fact that, alongside their American born lace worker colleagues, and the small Irvine Valley enclave employed at the Gouverneur lace factory, there was a significant English born (and evidently cricket-playing!) community living in the village. It is immediately striking that every single one of that community with an active lace making role in the factory in 1910, had strong connections with my home city of Nottingham, England or the wider county of Nottinghamshire. Nicol Young, of course, embodied the Scots, English and Nottinghamshire communities because he was part of them all, but the part that Nottingham played in embedding the lace industry in the United States, even for the comparatively short time that it existed, is made abundantly clear in these stories.

The other noteworthy aspect of these lives is that, apart from the odd fleeting visit, none of them returned to their homeland, choosing instead to put down their roots – to live and die – in the Unites States. The breadth of their different experiences and their individually unique stories, are, no doubt, resonant of immigrant stories generally, but lace making was clearly a transitory affair. I like to think, though, that when they did come together in one place for the purpose of making lace, that they were a talented and professional community who supported each other through the good and bad times. Anyway… let’s meet them:

Frederick Harry Goodyer was the Superintendent at the Gouverneur lace factory at the time of the 1910 census. He was born in Peckham, London on 18th April 1854, the son of a druggist. However, by 1871 the family had moved north to Nottingham and were living in the Hyson Green area of the town. By 1881 they had moved to the village of Attenborough and Frederick was employed as a Lace Warehouseman. He married Louisa Pace in Codsall, Staffordshire on 21st November 1883 and by 1891 they were settled in the Minster town of Southwell, Nottinghamshire, where Frederick, according to the census at least, was now the manager of a lace factory. The couple were back in the centre of Nottingham, living at 23 Clarendon Street by 1901, where Frederick was operating as a lace curtain salesman. This frequent changing of occupation was to be a feature of Frederick’s life.

Frederick and Louisa emigrated to America in 1903, arriving in New York City on the SS Teutonic on 30th January. At the time of the New York State census two years later, they were living in the city of Kingston, Ulster County, New York, with Frederick now a lowly labourer in the lace factory there. After their brief sojourn in Gouverneur in 1910 (where they lived on Austin Street), they were back in Kingston by 1920 where Frederick was now trying his hand at managing a boarding house. Whilst they stayed put in Kingston for another ten years at least, and where he became a naturalised citizen in 1923, Frederick clearly got bored easily… at the time of the1925 state census he was describing himself as a ‘farmer’. By 1930 he had reverted to being a salesman again – possibly hawking cleaning products (it’s difficult to read on the census entry).

Sometime before the 1940 census was taken, Louisa died. By then Frederick was living in the township of Rye, Westchester County, New York, apparently in a lodging house. He was eighty-six years old at that point and still describing himself on the census as a ‘Lace Manager’ in a ‘Lace Factory’, although presumably he had retired by then. Unfortunately, it is not clear from available records where Frederick saw out his final days.

Lace weaver James Hadfield was born on 14th December 1884 in Nottingham, the son of a shoemaker. At the time of his parents’ marriage in July 1884, James’ father John was living on Woolpack Lane, and his mother, Annie, on Goose gate. John emigrated to the US in 1888, and his family followed him out a year later. James was only four years old at the time. Like many lace making families making the journey to the US, they settled in Philadelphia, and, by 1900, they were living in Ward Thirty-Three at 339 East Indiana Avenue, not far from the Bromley mill. Around 1905 James made the journey to Gouverneur, where he married Grace Vaile on 23rd August 1906. Grace and James were to raise five children in Gouverneur, living for many years on Smith Street. He became a member of the local Masonic Lodge.

James was listed on the 1907-1908 roster of employees at the lace factory in Gouverneur and remained an employee of the factory for many years. A rare exception was during the 1928 to 1936 closedown, when, like others from the village, he relocated to Scranton PA. In 1930 he was resident at the same lodging house in Scranton as Irvine Valley Scot James Ross. He was to work in Scranton again after the final demise of the Gouverneur factory in 1944 and it was in Scranton, on 9th April 1961, that he passed away from heart failure at the age of seventy-six. Grace lived on until 1970. James and Grace are buried together in the Riverside Cemetery, Gouverneur (See Right – photo by Anne Cady via findagrave.com)

John Whyatt was born in March 1854, in Daybrook – the suburb of Arnold, Nottinghamshire that Nicol Young and his family (and indeed me!) later lived. He was baptised at St. Leodegarius Church, Basford near Nottingham on 10th April 1854. His father, also called John, was a ‘bleacher’ in the hosiery trade. John Jnr married Elizabeth Allen Christian at St. Andrew’s Church Nottingham on 26th June 1880. By this time he was employed as a ‘Warehouseman’. In 1881 they lived at 3 Cranmer Terrace, in the St. Anns area of the town. John travelled to the United States in 1889, arriving in New York City from Liverpool on the SS Alaska on 23 September of that year. Elizabeth followed soon afterwards.

Photograph taken from an article in the Wiles-Barre Times Leader, The Evening News dated 19th December 1970.

In 1900 the couple were resident in Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne County, PA. John was employed as a Weaver, at the Lace Mill there (see above). Despite not being shown in the roster of employees working at the Gouverneur factory in 1907-1908, John was resident there by the time of the 1910 census, which lists him as being a foreman at the lace mill. By 1915, however, the state census shows John and Elizabeth running a Boarding House at 36 William Street. They remained in Gouverneur, running their boarding house at 68 Clinton Street until 1931, in which year they both passed away – Elizabeth on 11th March and John on 12th August. They are buried in the Riverside Cemetery.

Allen Straw was born on 19th December 1870 in the town of Ilkeston on the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire border. His father, Samuel, was a stone miner, but by the age of twenty, Allen was working in the lace industry. He married Louisa Severn at Ilkeston on 13th February 1892. Louisa already had a daughter prior to their marriage and another four children, three girls and one boy, had arrived prior to them leaving for America. In 1901 they were resident in Cossall, Nottinghamshire and Allen’s occupation on the census was listed as ‘Lace Curtain Maker’.

Allen set off for America from Liverpool in the early summer of 1903. Louisa and the children followed three months later. Once they had disembarked at New York City, they headed straight for Gouverneur, making them one of the earliest of the 1910 cohort in our story to have made the journey there. Allen and daughter Mary Jane (known as Jennie) were listed on the roster of employees at the Gouverneur factory for 1907-08. In 1907 another daughter, Margaret, was born.

By 1913, however, the family had moved on again. In this year they are listed in the town directory for Zion City, Lake County, Illinois, for the first time, residing at 3002 Elizabeth Avenue. The city of Zion was only founded in 1900 and had a strict evangelical religious ethic. Amongst the business ventures that grew out of this was Zion Lace Industries with a large factory located on Deborah Avenue (a fifteen- minute walk from the Straw’s House). By 1946 they had retired to the neighbouring township of Waukegan, and it was here that Allen Straw died on 19 September 1946, aged seventy-five years. Louisa passed away on 28th April 1949 in her seventy-eighth year. They are buried together at Mount Olivet Memorial Park, Zion.

Lace mill machinist and fitter, Edwin Sidney Roberts was born at 47 William Street, Radford, Nottingham on 15th July 1877. His father, Samuel, was also a machine fitter in a lace factory. By 1881 the family had moved to the St. Ann’s area of the town. Here they initially lived just off Peas Hill Road, which had two lace factories dominating its skyline, according to the 1881 Ordnance Survey map of the area. Edwin lived at 9 Lilac Street at the time of his marriage to Flora Jane Cleary, at Emmanuel Church, St. Anns, on 1st November 1902 37.

The following year Edwin set sail for America, arriving in New York City from Liverpool on 19th November 1903. The passenger manifest suggests that Edwin is meeting someone in the city, possibly going by the name of M C Thomson (it’s not very legible), with an address at 511 Broadway. By the time that Flora followed him across the Atlantic in February 1904, with baby daughter Hilda Florence in tow (born in St. Ann’s on 4th February 1903), Edwin was staying at the Grove Hotel … in Gouverneur. Oddly, given that we know Edwin was resident in Gouverneur from around 1903, and that he was listed as a machinist working at the lace mill on the 1905 state census and the 1910 federal census, he doesn’t appear on the roster of factory staff for 1907-1908.

Flora gave birth to three sons during their time in Governeur – George Samuel on 9th September 1905, Sidney in April 1912 and Edwin Frederick on 4th April 1921. According to the census’s that took place between 1915 and 1925, Edwin was the lace mill superintendent during those years. When the Gouverneur mill closed in 1928, the family relocated to Kingston, Ulster County, New York. Here Edwin was employed at the United States Lace Curtain Mills which was founded in 1903 at 165 Cornell Street, at the junction with South Manor Avenue (the Roberts family lived on or around North Manor Avenue). The mill was part of the Scranton lace empire. Edwin died in Kingston on 24th August 1933 aged just fifty-six years. Latterly Flora lived with daughter Hilda (by then a teacher), and son Edwin Frederick (a Post office manager) in Floral Park village, Hampstead, Nassau County, New York. Flora died on 29th January 1944 in her sixty-third year. Edwin and Flora are buried, together with their son George (died 1973), at Wiltwyck Cemetery, Kingston, New York (See below – Photo: Donna Lamerson via findagrave.com).

Lace weaver Samuel Towlson (left) was born in Beeston, Nottinghamshire on 2nd March 1880. His father William was a lace maker in the town. Beeston had a rich tradition of hosiery manufacture going back to at least the very early nineteenth century and, in 1871, the Wilkinson family opened the Anglo-Scotia mills on Wollaton Road, which signalled the arrival of power-driven factories to the town38. David Hallam’s 2014 blog post on lace making in Beeston covers the history in studious detail and puts the Wilkinson family (who we shall meet again later in this story) in context39.

At the time of the 1891census the family were living at 24 Willoughby Street in a household that also included fellow 1910 Gouverneur weaver Ernest Hardy (see below). The Towlson family (including Ernest Hardy but minus their father William, who was already in the US) arrived in New York City from Liverpool on 28th March 1892, bound for Connecticut. They were heading there because William Towlson’s Beeston employer, the aforementioned Wilkinson family, had purchased real estate in Tariffville, Hartford County for the purpose of manufacturing lace. Several key workers – including William – were shipped out from Beeston to supervise the production of lace curtains at the site. In Tariffville, on 28th July 1894 another child, Harold Percival, was born to William and his wife Maria. Unfortunately, William died on 12th February 1895 and the family began to go their separate ways.

By 1905 Samuel Towlson was resident in Gouverneur after recently marrying local girl Nina May Campbell, on 19th April 1905. With a couple of exceptions he was to see out his life there. It seems odd then that his name doesn’t appear on the 1907-08 roster of factory employees. Together, Samuel and Nina raised two sons, Earl (born 4th April 1906) and Harold (born 17th June 1908). Sadly Nina died, in her forty-first year, on 1st March 1925. Samuel wasn’t a widower for long, however, and on 7th May 1927 he married Pearl Adele Campbell (nee Forsythe) also in Gouverneur.

In 1928, following the first closure of the lace factory, and like many of his colleagues, Samuel took his family to Wilkes-Barre in Pennsylvania in pursuit of work. It would seem that he returned to Gouverneur for a spell in 1931. He is quoted in a news-piece in the Gouverneur Tribune Press 40 regarding a letter received from motor manufacturer Henry Ford enquiring about one of the old looms in the now idle lace factory. Samuel is described as “recently returned here from Pennsylvania where he has been engaged in the lace business.”

In the article Samuel talks about the history of the loom:

“The loom referred to by Mr. Ford… is evidently the loom that came to this country in 1888 from England. That was the first loom to come here. At first it was installed in a mill at Derby, Connecticut, and later in another place in Connecticut 41. My father worked on the loom before me and when the local mill was running, I also operated it. The loom was sent here [i.e. to Gouverneur] in 1908 and installed in the local mill. It is a 300-inch machine and was not used as extensively as other looms. Mr Ford must be trying to purchase the loom solely on the fact that it is the first one to come to America and not on the strength that it is the first mechanical lace weaving loom to be manufactured, for the latter piece of machinery was made in 1874 and is now located at Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.”

The 1940 census infers that the family had relocated again, this time to Kingston, Ulster County, New York by 1935. However, the re-opening of the factory brought them back to Gouverneur for the final time and he is shown on the above 1937 photograph of mill workers at Gouverneur. By 1940, the Towlsons were resident at 55 Prospect Street.

Pearl Towlson died on 8th October 1955 aged sixty-seven years. Typically, Samuel moved quickly to find another wife and he married Percie Kinney (nee Laforty) in Gouverneur on 20th October 1956, almost exactly one year since Pearl’s death. Percie died on 5th August 1967 aged eighty-three. She shares a grave at the Riverside Cemetery with Samuel, who died in Gouverneur on 19 March 1972 aged ninety-two. Samuel’s grave is shown right. (Photo: Anne Cady via findagrave.com)

Lace Weaver Ernest Henry Hardy was born on 13th May 1883 in Long Eaton on the Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire border. By 1891 he was living in Beeston, Nottinghamshire, at 24 Willoughby Street, in the same household as fellow future Gouverneur weaver Samuel Towlson. It appears that he was related to Samuel’s mother Maria, whose maiden name was Hardy (although the exact relationship is not clear from the sources). Ernest travelled to America with the Towlson family (listed on the passenger manifest as “Master E. Toulson”). They arrived in New York City, from Liverpool, on 28th March 1892. The party moved on to Connecticut – to Tariffville, where a new lace factory was being established (see the entry for Samuel Toulson above). Members of the family seem to have gone their separate ways, however, after the death of patriarch William Towlson in 1895. Ernest was naturalised as an American citizen in Simsbury, Connecticut on 22nd September 1904 and his next appearance in the records is his marriage to widow Emily McFetrich (nee Campbell), a native of Gloucestershire, England, in Manhattan on 28th April 1909.

Their appearance in Gouverneur the following year was fleeting. They resided at 271 West Main Street where they had taken in Irvine Valley Scot James Cox as a lodger. As early as 1911, according to city directories of the time, they had moved on to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where their son, Walter Arthur, was born on 20th September 1914. By 1920 they had moved on again, this time to Philadelphia, and they were ensconced at 225 East Lippincott Street in Ward Thirty-Three, before moving on to 1021 East Shelmire Street, where Ernest died on 2nd August 1924 of Chronic Nephritis, aged forty-one years. Emily lived on at East Shelmire, where she died aged seventy-three on 28th September 1950.

Lace Weaver Thomas Higgins was born on 18th August 1867 in Newthorpe, Nottinghamshire. His father – also called Thomas – was a miner, and the family lived at ‘Skegby Bridge’ near Mansfield at the time of the 1871 census. By 1881, however, Thomas’ mother, Louisa, had moved the family to Radford in Nottingham and was describing herself on the census as widowed (note that I am unable to find any record of Thomas’ father’s death).

It was whilst in Nottingham that Thomas began working in the lace industry… the 1881 census records him being employed as a ‘Lace Dresser.’ On 5th April 1890, Thomas married Annie Marshall at Hyson Green church, Nottingham. Between March 1891 and January 1902 Annie gave birth to four children – Thomas Marshall, Elsie Lucile, Philip Frank and John William. The 1901 census records Thomas’ occupation as ‘Lace Curtain Maker.’

The family emigrated to America in 1903 and by 1905 were resident on West Main Street in Gouverneur. Thomas is listed on the roster of weavers at the mill for 1907-08, with his son, Thomas Marshall, also shown (detailed under ‘Other Help’). By 1910, daughter Elsie was also working at the mill and Philip and John followed them into the mill in subsequent years.

Although Thomas and Annie appear on the federal and states census’ for 1905, 1910, 1920 and 1930 and are shown as living in Gouverneur, there is no entry for them for 1915. This could be explained by the fact that Thomas’s naturalisation was ratified at Waukegan, Illinois on 3rd April 1914. Waukegan is a township adjacent to Zion – and so it is likely that, for a short time at least, Thomas sought employment at the factory run by Zion Lace Industries there. Thomas died in 1936 in his sixty-ninth year and is buried in Pieces Corner Cemetery, Macomb, St. Lawrence County, New York. Annie moved to Philadelphia to live with son Philip, and she died there, aged seventy-nine, on 29th January 1946. She was buried with Thomas at the Pieces Corner Cemetery.

Of his Gouverneur lace-making children: Thomas Marshall Higgins married twice and eventually put down his roots in Scranton, Pennsylvania, working in the lace factory there. He died on 27th January 1956 aged sixty-four, barely a month short of his planned retirement date. He is buried in Gouverneur. Elsie married cheesemaker Ivon Hull in Canton in 1917. They lived in Canton, Harrisville and Gouverneur at various times. Elsie died in nearby Watertown, Jefferson County, New York on 11th June 1982, aged eighty-eight years. Philip moved to Philadelphia and lived at 3301 North Sixth Street in Ward Thirty-Three, in the heart of the city’s mill district. He died on 14th February 1962 aged sixty-four. John broke away from lacemaking and became a bus driver, eventually moving to Syracuse, New York. He died there on 17th July 1962 aged sixty-two years.

Where the Irvine Valley lace-makers in Gouverneur had the Smith brothers and the Ross brothers amongst their number, the English community had the James brothers:

Charles Wilkinson James and George James were both born on Meal Court, off St. James Street, Nottingham – Charles on 14th March 1856 and George on 5th November 1857. Their father, John Joseph James, was also a lace maker. Their mother, Charlotte, was a member of the Wilkinson lace making family of Beeston – her brother Frank was a leading presence in the industry locally, so lace was in very much in their pedigree. Uncle Frank Wilkinson was also the driving force behind the resurrection of the lace factory at Tariffville, Connecticut, USA, which has already featured in this story, so much so that it was known locally as the ‘Wilkinson’ mill.

Lace weaver Charles married Elizabeth Leavers (or Leivers) on 4th November 1875 at St. Thomas Church in Nottingham. He was, according to the marriage entry, living on Mount Street at the time. Soon afterwards they moved to Beeston, where six children were born to them: Lily (1876), Florence (1878), John Edward (1880), Mabel (1883), Mary Elizabeth (1885) and Rosie (1890) 42.

The family made the move to the United States in 1892 – with Charles and Elizabeth travelling out first. The children followed on SS Servia, which left Liverpool for New York on 4th March 1892, arriving twelve days later43, under the care of a mysterious ‘Matron’ called Mary James. Things don’t seem to have gone to plan at first.

Eight years after their arrival in America, the 1900 federal census shows Elizabeth, Mabel and Florence living in Chester, Pennsylvania at 3021 West 3rd Street. By then Florence is already a widow at the age of 23. The lace mill in Chester was a prominent employer in the town, and it had Nottingham connections, so it is easy to imagine that Charles may have worked there. However, on census night the indications are that Charles was being held in Connecticut State Prison44, in the town of Wethersfield. I am unable to find any record of what Charles’ offence might have been. However, as we already know, the Wilkinson family did have a strong connection to Connecticut through their ownership of the Tariffville lace mill. In addition their daughter Rosie (by then going by the name of Mae), had been adopted by a family living in Hartford, Connecticut. Of course, we don’t know the background to why the James’ youngest child was, in effect, given away. It may have been an extreme indicator that the family were struggling financially. Whatever the reason, the hope is that it was done in the best interests of their daughter, who was only ten years old in 1900. Son John Edward is recorded on the census working as a lace weaver at the mill in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania at this time, but there is no confirmed trace of their eldest daughter Lily in the records at all, after their arrival in the US. So, at this point in the summer of 1900, the family has scattered and, outwardly at least, appeared to be in a desperate position.

Despite this obvious low point, the James family (minus Lily but including Mae) were reunited once more by 1905, where the the New York state census shows them residing on Hailesboro Street, adjacent to the lace factory, in Gouverneur. Charles’ brother, George was also living with them (this is just prior to George’s wife, Maria, joining him in the US).